Healthy Aging and The Social Determinants of Health

March 2022

by Aaron Guest, PhD, MPH, MSW

Assistant Professor of Aging

Center for Innovation in Healthy and Resilient Aging

Arizona State University

In the opening pages of his 2015 book, The Health Gap, Dr. Michael Marmont asks, “Why [do we] treat people and send them back to the conditions that made them sick?”. Encapsulated in this question is something those of us in public health and health care take for granted today. It is the recognition that the social, cultural, built, and natural environments that an individual exists in affects health. Collectively, we call these factors the social determinants of health.

Multiple definitions of the social determinants of health exist. The most-oft cited comes from the World Health Organization, which defines the social determinants of health as “the non-medical factors that influence health outcomes. They are the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age.”

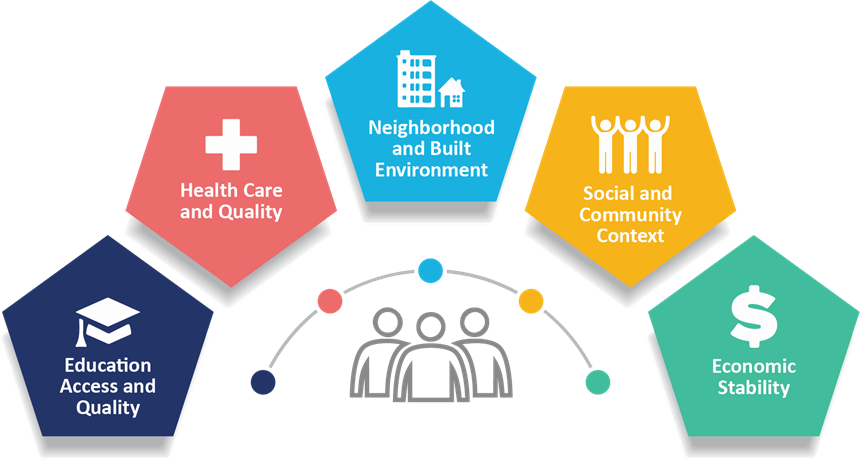

We often further refine the social determinants of health into five co-equal domains:

- Education Access and Quality, including access to primary, secondary, tertiary, formal and informal, and continuing education.

- Health Care and Quality, including public health preventive services and the ability to prevent and treat acute and chronic illnesses.

- Neighborhood and Built Environment, including the environmental exposures and the methods in which an individual’s environment promotes or discourages favorable health outcomes.

- Social and Community Context, including an individual’s social supports, feeling of belongingness, access to community members, engagement in community activities, and ability to live authentically.

- Economic Stability (and Policy), including a person’s ability to provide for themselves and afford all necessities. Within this domain, many of us are now including policy as a determinant of health, rather than having it be subsumed elsewhere.

(CDC, 2021)

Returning to the WHO definition, notably, this definition recognizes that the social determinants of health are not static. They do not influence our health and wellbeing at only one point in time. We interact with them throughout our lives as we age. They are cumulative. The accumulation of our exposures to the social determinants of health results in what Dannefer (2003) refers to as the Cumulative Advantage and Cumulative Disadvantage. While often discussed only in relation to inequities, the social determinants of health result in both positive and adverse health outcomes. Our exposure to various social determinants of health influences the cumulative advantage/disadvantage we have as we enter older age resulting in the disparate health outcomes we experience.

Historically, we have only looked at the social determinants of health outcomes – what we call the downstream effects. For example, the CDC estimates 29.2% of individuals over age 65 have type 2 diabetes, up from 26.8% in 2013. Our efforts have traditionally focused on ensuring appropriate treatment and access to health care for these populations. Increasingly, we are now looking at the upstream causes of these outcomes. We know that people with less than a high school diploma are nearly twice as likely to develop diabetes than those with at least a bachelor’s degree. How do we address the interrelated educational, economic, and social domains to prevent diabetes in older age? How do we ensure individuals live in neighborhoods and community contexts that promote physical activity? And, how can we support midstream corrections through policy and health promotion

Indeed, the health conditions and health inequities we see among our older populations result from exposure to an individual’s personal social determinants of health throughout their life. We must take a life-course view in addressing the social determinants of healthy aging. Yet, this understanding is relatively recent in our collective consciousness – emerging to the forefront of policy in only the last thirty years. Returning to the quote that opened this piece, allow me to now offer the full selection: “Why [do we] treat people and send them back to the conditions that made them sick? We need to treat people, but we need to address the issues that make people sick.” To do so, we must address the adverse social determinants of health – and in doing so, provide for a healthier aging experience for all.